History of the creation of Solana

The foundational network was established in 2017, with the first test blockchain version launched in 2018.

Solana was founded by three partners: Greg Fitzgerald, Eric Williams, and Anatoly Yakovenko.

The foundational network was established in 2017, with the first test blockchain version launched in 2018.

Solana was founded by three partners: Greg Fitzgerald, Eric Williams, and Anatoly Yakovenko.

In 2017, Yakovenko published a draft of the project’s white paper, introducing the Proof-of-History (PoH) blockchain synchronization algorithm. Later, Yakovenko, together with his former Qualcomm colleague Greg Fitzgerald, created a blockchain using the Rust programming language that employed PoH as its “internal clock.” In February 2018, Yakovenko and Fitzgerald released the project’s official white paper and launched the first internal testnet.

In the white paper, Yakovenko outlined the primary goal of Solana: to reduce the time required for blockchain nodes to synchronize or achieve consensus. This high speed was intended to help developers scale their decentralized applications and enable them to quickly grow their user base.

In 2018, Yakovenko and Fitzgerald founded the company now known as Solana Labs. The project team includes former engineers from Google, Microsoft, Qualcomm, Apple, Intel, and Dropbox.

Initially, the project was named Loom, but it was later renamed Solana to avoid confusion with the Loom Network, a Layer 2 solution. The project was named after Solana Beach, a small town 30 minutes from San Diego, where Anatoly Yakovenko lives.

From April 2018 to July 2019, the project raised over $20 million in venture investments through several private token sales. In the third quarter of 2020, the public testnet Tour de SOL was launched. In March 2020, the beta version of the mainnet went live.

In June 2020, the Solana Foundation was established. Its primary goal is to support the effective development of the project’s ecosystem. Solana Labs transferred 167 million SOL tokens and all intellectual property rights to the Solana Foundation. A month later, the project managed to attract significant attention from investors and users.

In October 2020, Solana’s developers launched a cross-chain bridge with the Ethereum blockchain. This technology’s primary advantage is its ability to transfer assets between two separate blockchains.

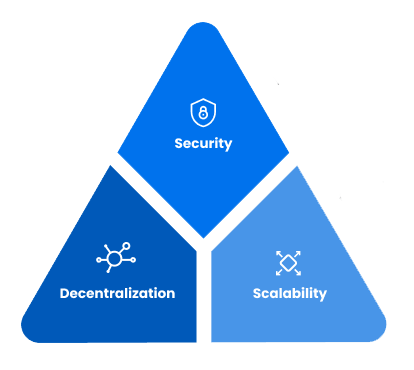

For years, the team worked on solving the difficult challenge of achieving balance between three key parameters: Decentralization, Security, Scalability.

The latter was particularly lacking in other blockchains. While they were decentralized, reliable, and secure, they were difficult to scale. As blockchain ecosystems grew, maintaining acceptable system speeds became increasingly challenging.

However, Solana was designed as an alternative payment system, where speed was as critical as security.

This challenge was resolved: the team managed to ensure high-speed performance without compromising security.

To achieve maximum scalability, Solana utilizes what it refers to as eight “key innovations” that make it the first web-scale blockchain ecosystem. These computational technologies support thousands of node operators, allowing transaction throughput to scale proportionally with network capacity.

To accelerate system performance, Solana uses its proprietary Proof-of-History (PoH) algorithm alongside Proof-of-Stake (PoS).

Proof-of-History is a crucial and even somewhat revolutionary technology, so let’s take a closer look at it.

One of the main challenges in cryptocurrency networks is node synchronization. The speed of synchronization directly affects the blockchain’s throughput: the faster it is, the more transactions per second the network can process. To synchronize time, a reliable clock is needed. Cryptocurrencies have their own internal time system—timestamps. However, these timestamps are not always accurate because there is no central clock to reference. This creates synchronization issues: if timestamps are used as a reference, a new block might appear before the previous one.

Proof-of-History is not a consensus mechanism but rather a way to optimize the time required to confirm transactions and establish their order. It works in tandem with Proof-of-Stake.

PoH acts as a decentralized clock, solving synchronization problems.

In Bitcoin’s blockchain, which uses the Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus algorithm, blocks contain large groups of unordered transactions. The date and time a miner assigns to a block depend on their local time zone. As a result, timestamp data can vary between nodes and sometimes be inaccurate. This discrepancy necessitates additional verification of timestamps, which consumes computational power and slows down the network.

In contrast, Solana’s transaction placement mechanism eliminates the need for validators to conduct extensive timestamp verification, making transaction processing significantly faster than in Bitcoin.

Proof-of-History enables Solana to:

PoH also plays a role in data storage within the ledger.

Ultimately, Solana’s blockchain is designed to achieve maximum transaction speed without sacrificing decentralization.

Solana claims its blockchain can handle over 50,000 transactions per second (TPS) under peak load, making it one of the fastest blockchains in operation today.

For comparison:

Developers believe that in the future, Solana could reach speeds of over 700,000 TPS.

Additionally, Solana reports that the average block time is 400 to 800 milliseconds, while the average transaction fee is just 0.000005 SOL.

Beyond Proof-of-History (PoH), Solana’s high-speed performance is made possible by several additional technologies:

Thanks to this diverse set of technologies, Solana does not require sharding or second-layer (Layer 2) solutions to maintain its speed and scalability. This allows developers to build applications directly on the blockchain, making transactions thousands of times faster than on Ethereum or Bitcoin.

This, combined with its immense scalability, makes Solana well-suited for hosting decentralized applications (dApps) that can potentially support tens of thousands of concurrent users without experiencing performance issues.

Solana achieves this level of scalability without relying on second-layer technologies, off-chain solutions, or any form of sharding. This makes it one of the few Layer 1 blockchains capable of reaching over 1,000 transactions per second (TPS).

Unlike some platforms, almost anyone can become a Solana validator and contribute to securing the network. The process is entirely permissionless, though users must maintain a server that meets minimum hardware requirements. Currently, the network boasts over 1,000 validators, making it one of the most decentralized blockchains in existence.

Like most blockchains, Solana has its own native token (SOL), which is used to pay for transaction fees and smart contract execution.

The SOL token standard is known as SPL, similar to ERC-20 in Ethereum. Holders of SOL can also become network validators. To maintain a deflationary model, Solana periodically burns a portion of SOL tokens to counteract inflation.

The smallest unit of SOL is called a Lamport, named after the computer scientist Leslie Lamport, whose research laid the foundation for distributed systems theory. One Lamport equals 0.0000000000582 SOL.

There are three primary use cases for SOL:

Solana’s deflationary model ensures that a portion of SOL tokens is periodically burned to help control supply.